Black Hole Digital Hologram

Black hole visualization is not new, with the earliest work (to my knowledge) done in the late 70s[1]. In 2014, Interstellar brought black hole visualization to the masses with the spectacular and mostly scientifically accurate rendering of the black hole Gargantua. Moreover, the internet is full of black hole visualizations. It's therefore a fair question to ask - given the sheer quantity of content out there, why bother producing even more?

To me, the answer is that none of the existing visualizations - not even Interstellar - achieves the level of realism that is possible with a hologram. Even simple stereo 3D would be a major jump in realism, and yet it is nowhere to be found (there is a bit of a rub here, which is that we don't a priori know that black holes don't break stereo 3D - we'll come back to this). Full-parallax digital holograms, when done well, have the capacity to achieve a level of realism that goes far beyond stereo 3D, yet the visualizations currently out there don't even achieve the latter.

Some full color holograms are so realistic that if nobody told you, you wouldn't know that you are looking at a hologram. To me, nothing demonstrates this more aptly than the piece below[2] by Philippe Gentet, which he showed to me at his lab in Seoul. Telling me that one of the figurines was genuine and the other a hologram, he asked me to guess which is which. Answering (honestly) that I had no idea, he then adjusted a knob, causing one of the figurines to dim. I fell for the trick an stated that the dimmed figurine must be the hologram (it wasn't).

I'm not going to try and argue that my black hole hologram succeeded in achieving the realism of the piece above - rather, this is an argument that digital holography may be the optimal medium for black hole visualization, and that it's worth a shot.

A big difference between this project and the 3D Apollonian gasket, is that in the case of the former I could get away with not understanding much about how digital holograms work. Specifically:

1. The details of the Chimera Holography 3D Studio Max script for generating images of the 3D scene, and

2. The details of how these images are then turned into a digital hologram,

were both black boxes that I didn't need to understand. However, for a black hole, I would need to understand both. The reason for the first point is because - to the best of my knowledge - there is no way of importing a black hole into 3D Studio Max. As we will see, you need to write your own custom graphics engine, and that means you have to understand the Chimera script well enough to implement it inside your engine. The reason for the second point is more nuanced and we will get to it at the end.

When I began this project, it wasn't even clear to me that black holes would "work" in stereo 3D. As I alluded to above, it was entirely possible that the disortion they produce would simply prove too confusing for our brains to make sense of. In fact, the sheer absence of stereo 3D black holes images on the internet could be viewed as evidence that this is indeed the case, and the one paper on the topic that I managed to find seemed to think so[3]. So, the first step was to successfully produce a black hole stereo pair. This was an "off-ramp" for the project in the sense that if it failed, a hologram would fail for the same reason and there was no point in continuing.

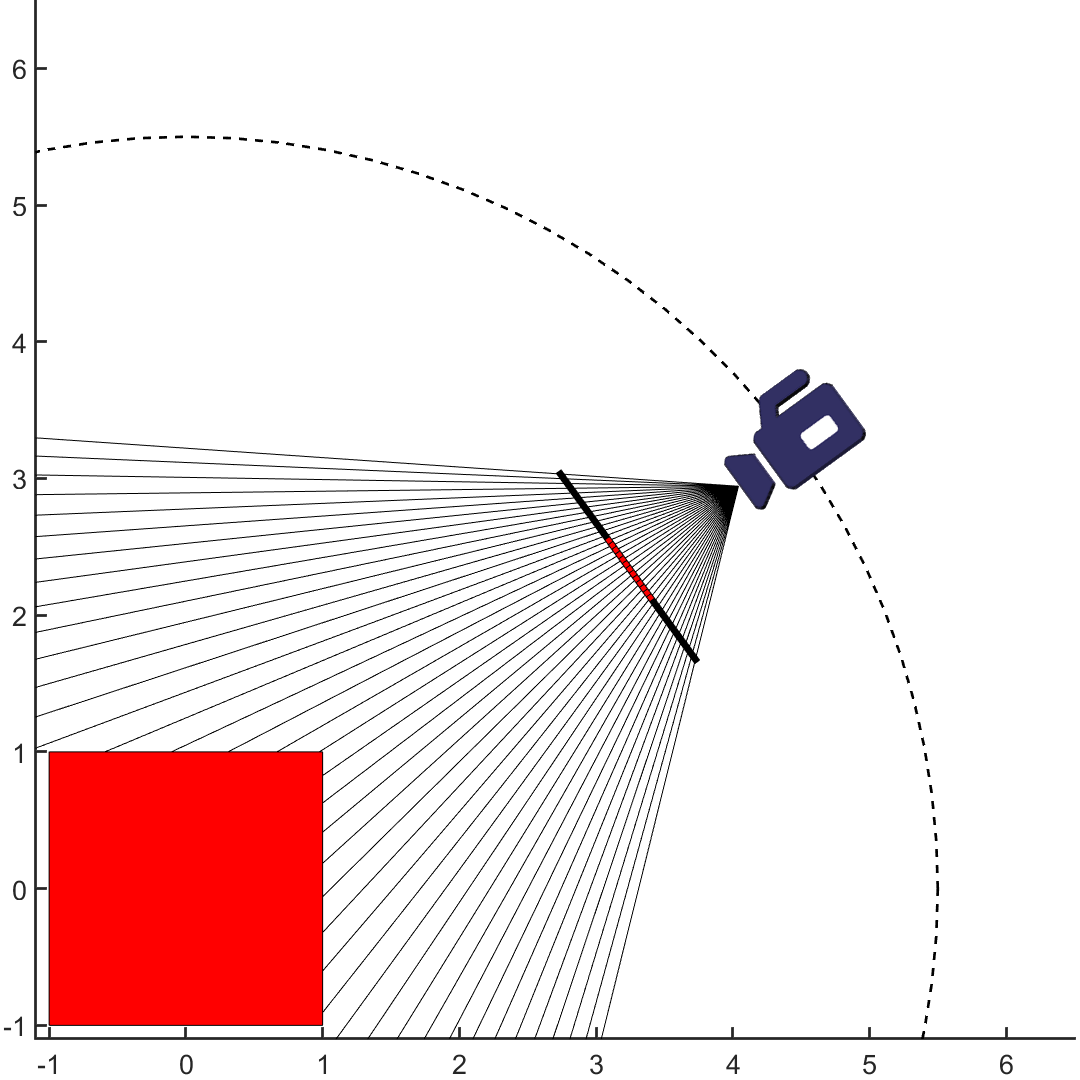

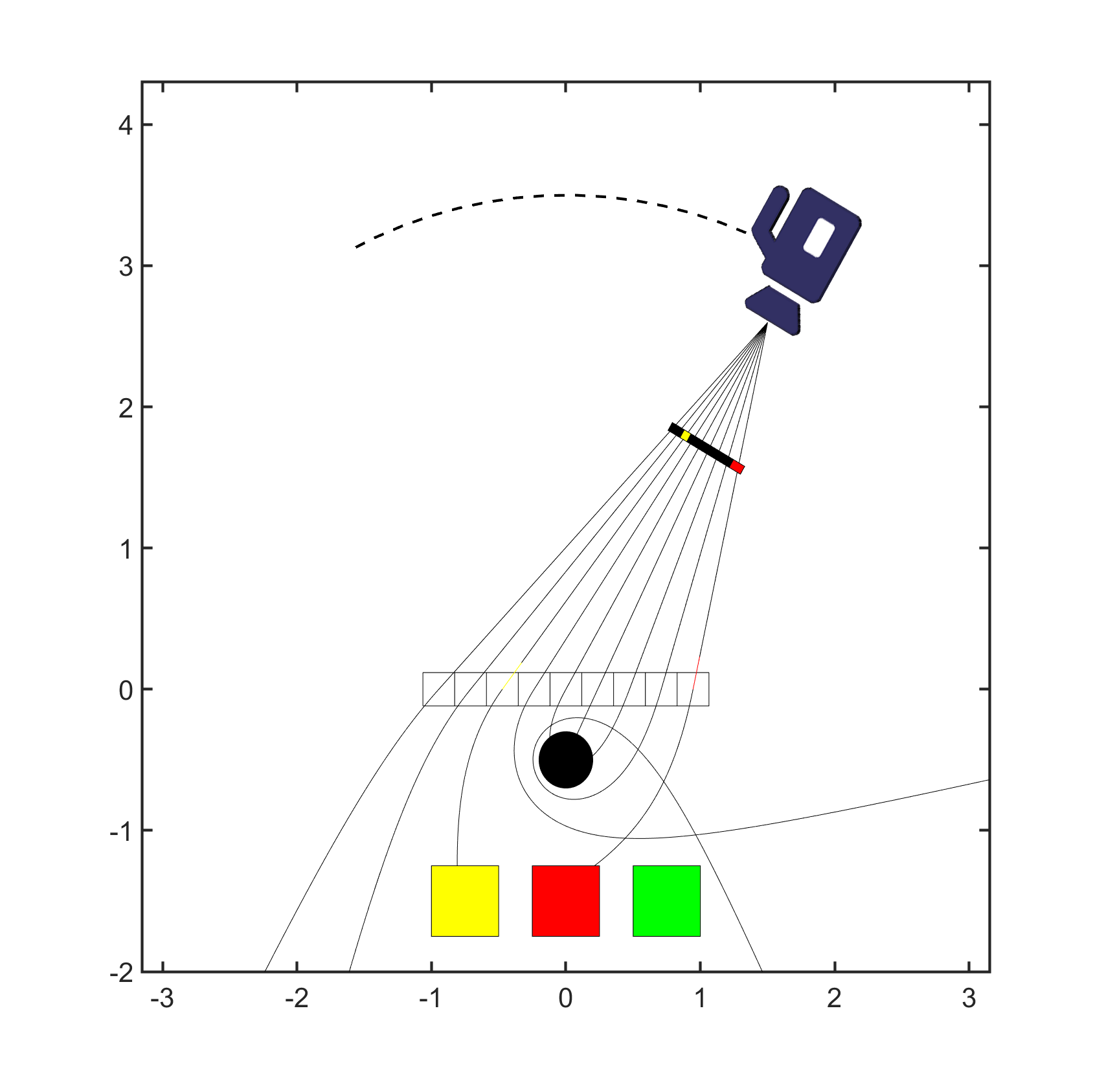

Black holes are visible mainly because they bend light. To the best of my knowledge, it is not possible to

render one within rasterization based rendering engine like 3D Studio Max or Blender. You need to use a

raytracer, and you need to modify it so that the rays move along curved trajectories defined by the geodesic

equations of the black hole - this is called nonlinear ray tracing and is illustrated below. I will

not

go into the details here other than to say that nonlinear raytracing has been well understood for decades, is

simple enough to implement that a talented high school student could do it, and to provide the following

reference[4].

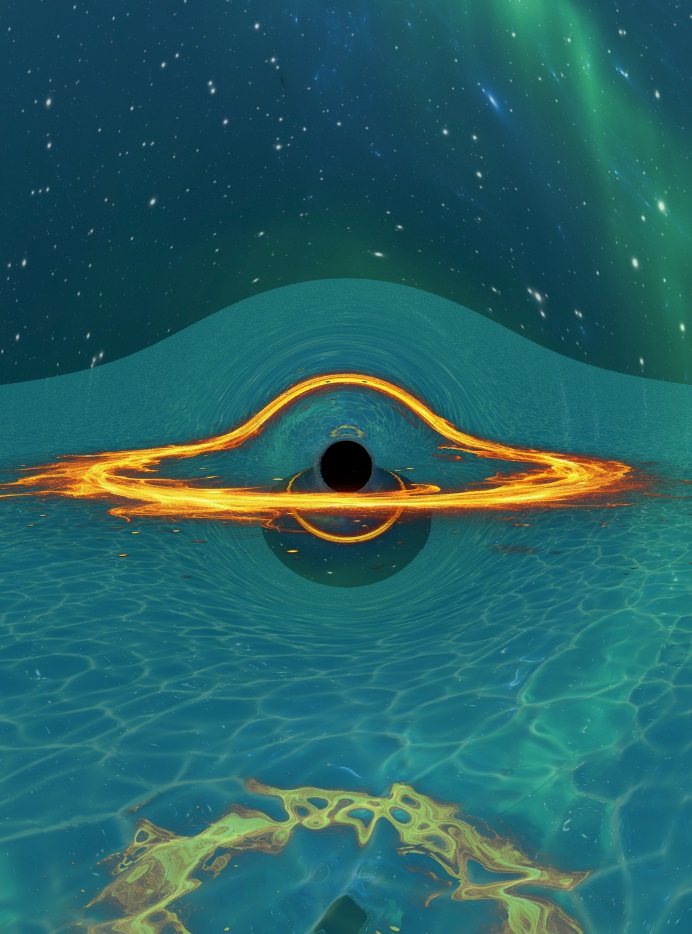

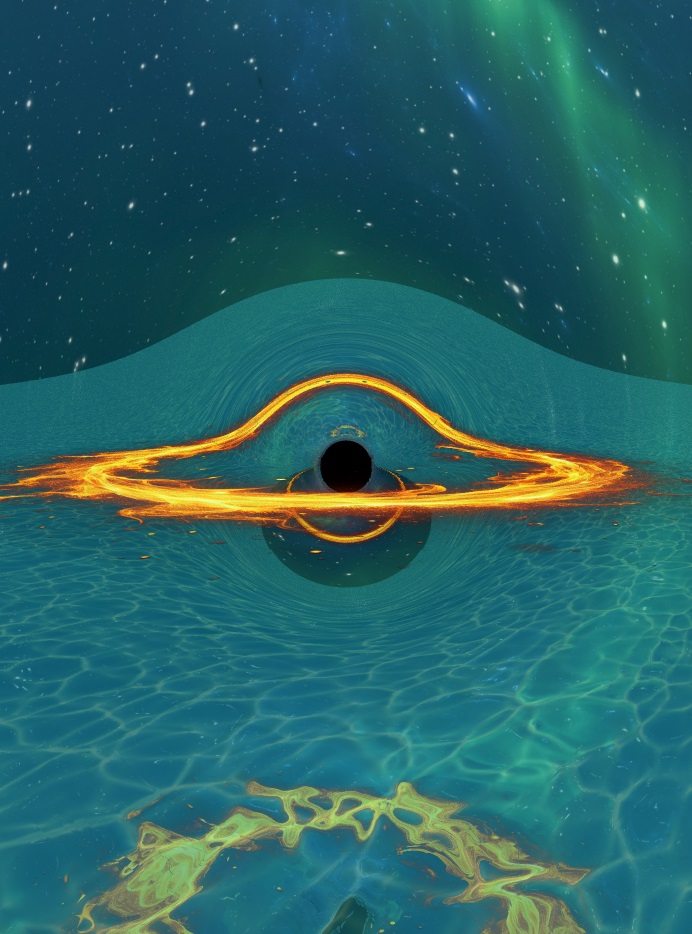

I have a raytracer which I have been maintaining since undergrad. I had previously given it the ability to

render black holes under the simplifying assumption of an environment at infinity; however, to

generate an interesting stereo pair, I needed to have an environment a finite distance from the black hole. I

made the necessary changes to the code and initially settled on a black hole hovering over an

infinite ocean, surrounded by a firey accretion disk and with an aurora in the background (as per the two images

below). To my relief, the 3D worked. To view the 3D yourself, simply cross your eyes as per the technique here. If you

succeed, you should notice

that the black hole itself looks a bit like a marble, and that the sky behind the black hole seems to bend

backwards into the screen.

This was good news - it meant that a black hole hologram could be built in principle. However, by this point I'd had a chance to take Jacques Desbiens's course in digital holography, and knew as a result that my current setup wasn't going to work. For reasons which at the time of writing I still do not understand, digital holograms suffer from holographic depth of field: objects exactly at the hologram plane are perfectly in focus, whereas as you move either in front of it or behind it they go out of focus. Strictly speaking, all holograms suffer from the problem to a greater to lesser extent, but it is particularly severe in the case of reflection digital holograms, which is what I was making (conversily, it is practically non-existent for transmission analog holograms). In my case, the rough rule is if your holographic plane has width w and height h, then objects in your 3D scene should be placed no more than one third of max(w,h) in front of the holographic plane, and no more than two thirds behind it.

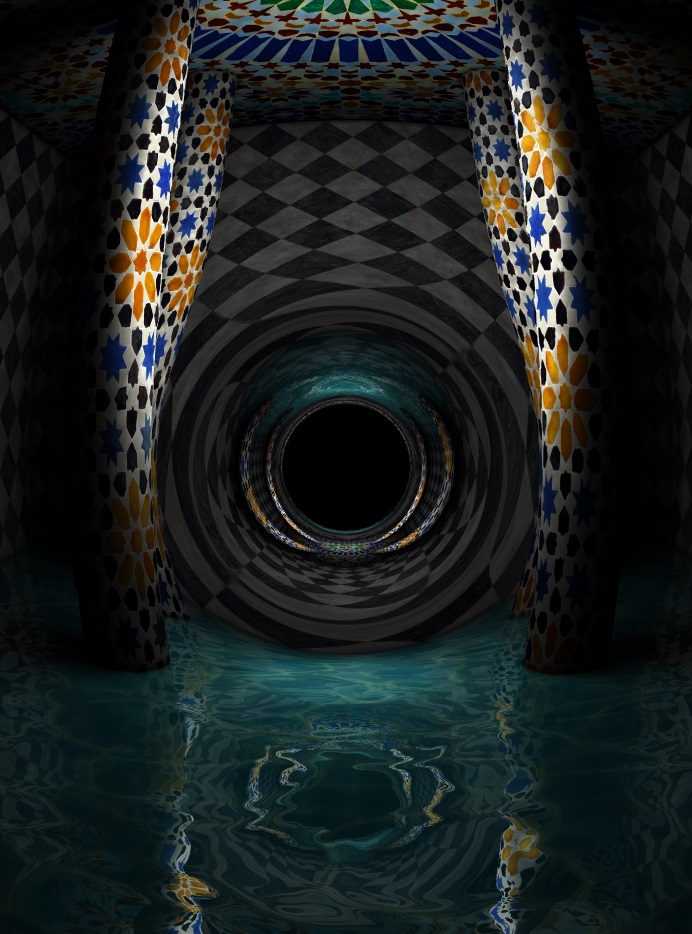

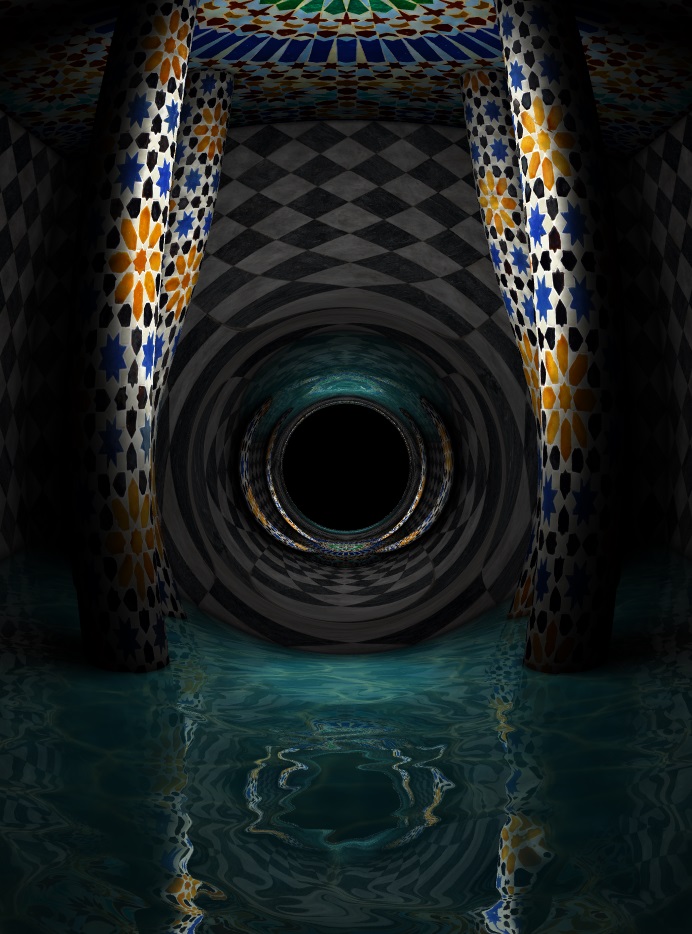

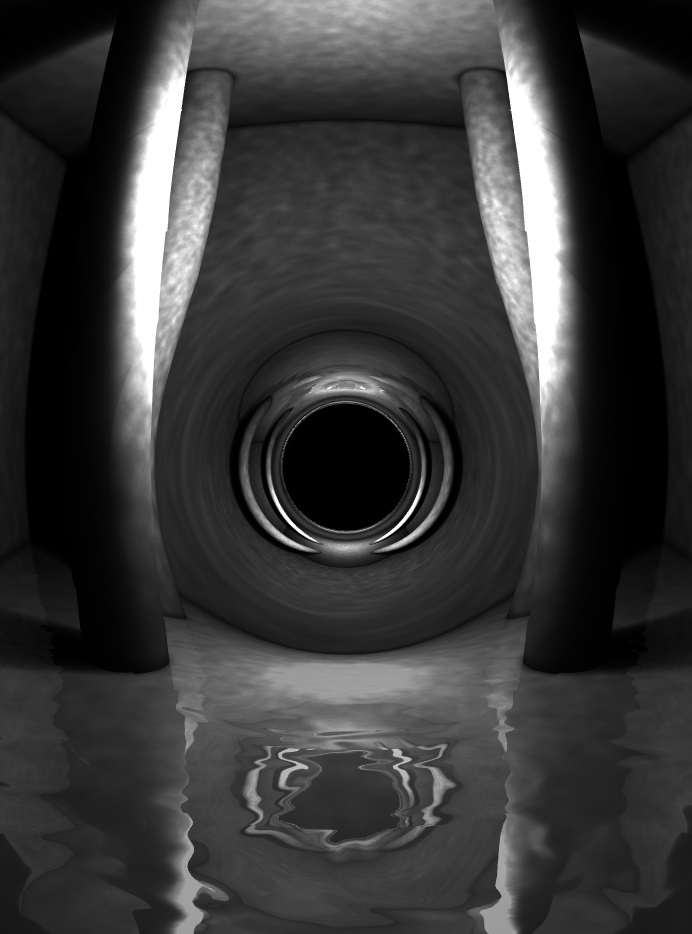

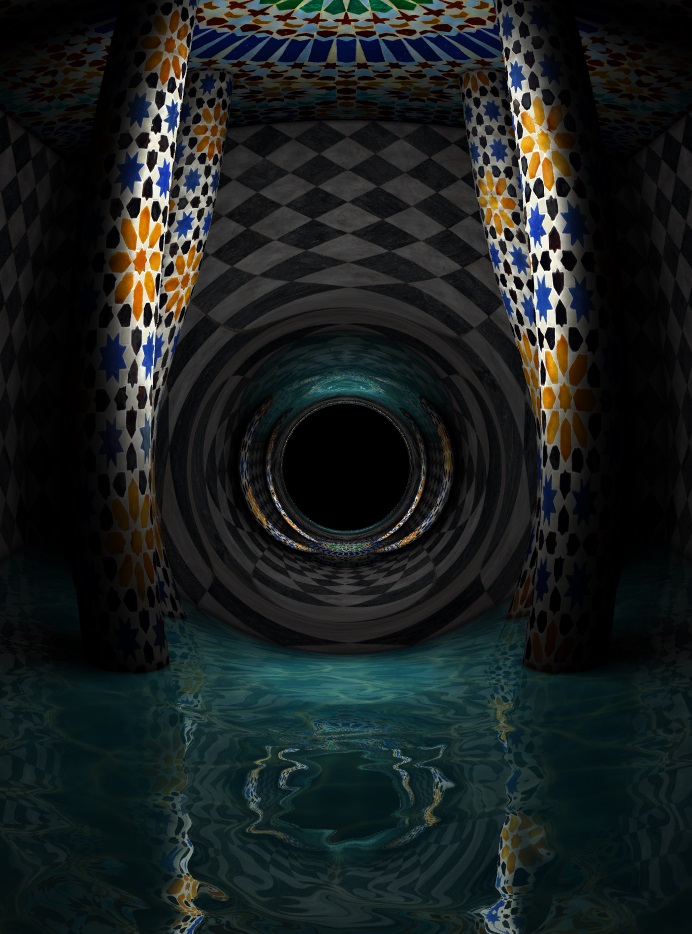

This meant that my ocean extending out to stars at infinity was going to be a problem. I decided to keep the basic idea of a black hole hovering over water, but to enclose the water within walls to form an underground chamber. Drawing inspiration from my vague memories of visiting the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul twelve years earlier, I added pillars coming out of the water covered with Islamic tiles - I applied a similar Islamic tiling to the ceiling. For the walls, I stuck to a simple checkerboard pattern, which I felt made the optical distortion induced by the black hole (which I had hovering in the air between the pillars) stand out more. The result is illustrated both in the stereo pair above and in the three renderings below. The the case of the latter, I've intentionally separated things out into the result with no shading, the result with shading alone, and the overall result. This is because accurate shading of the environment surrounding a black hole is non-trivial and has interesting properties that I want to discuss.

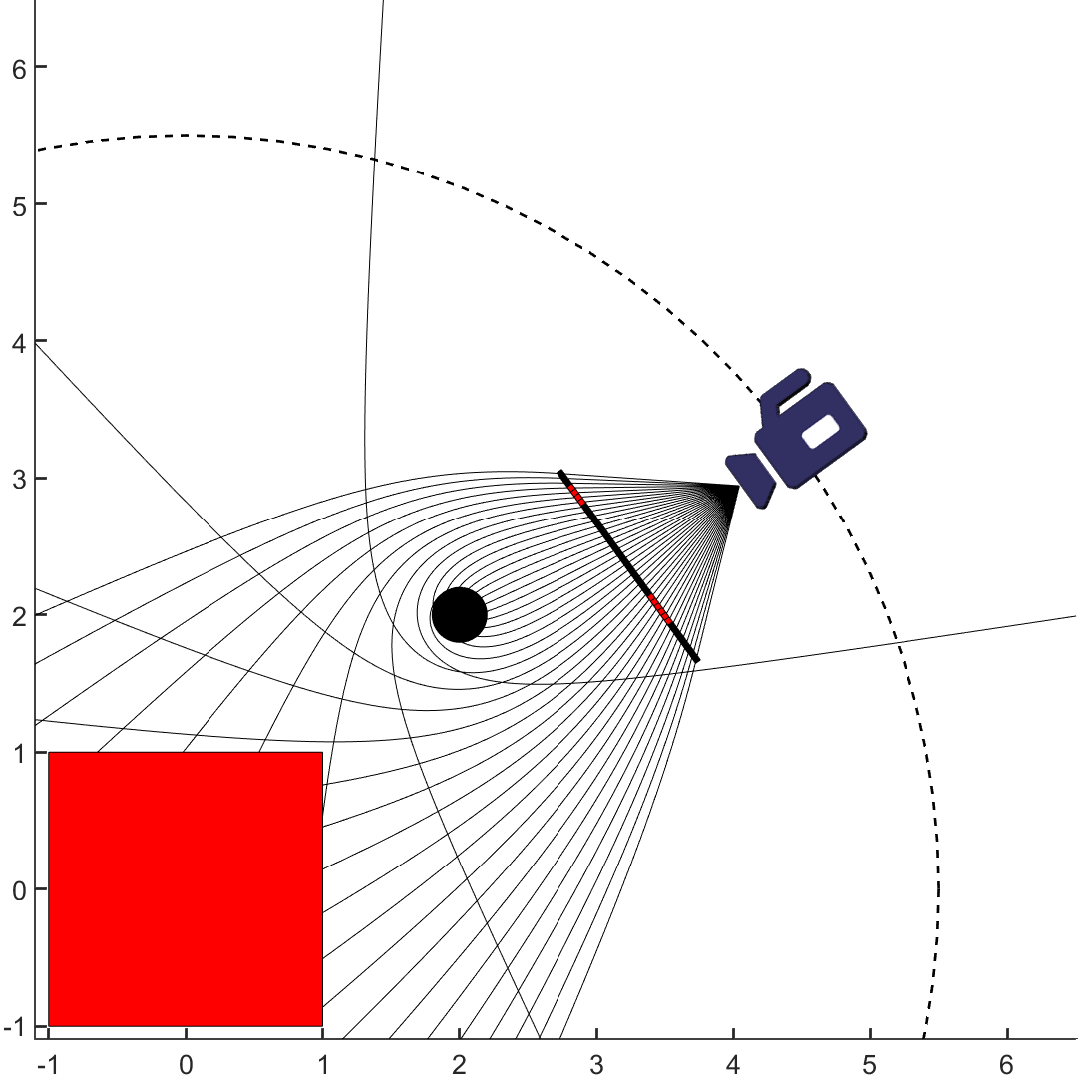

When one does shading in a raytracer, the typical approach is to find the straight line joining a point to be shaded with a light, and then to shade based on the distance to the light as well as the angle with which the light ray strikes the surface. This becomes enormously more complex when one is dealing with a black hole, because:

1. Finding a light ray connecting two points in a black hole spacetime is non-trivial.

2. It turns out that there are typically infinitely many such light rays.

To handle this, I decided to use a non-linear variant of the Photon mapping[5] algorithm. In brief, Photon mapping works by casting a large number of light rays from each light in a 3D scene into the scene, and keeping track of where they land. When shading a point, one then simply counts how many photons have landed "nearby". This approach neatly sidesteps the thorny issue raised above.

Photon mapping is famous for its ability to render realistic caustics - that is, bright areas in a scene where

light has been focused by something like a glass sphere. I had wondered for a long time whether or

one might similarly get "black hole caustics" due to the focusing of light by a black hole. The answer is yes -

this is precisely the bright spot on the surface of the water in middle and right images above. In this case,

the light (invisible) is directly

above the black hole (close to the ceiling) and it gets focused to a point on the water surface directly below

the black hole as it curves around it. This is perhaps easiest to see it by looking at a map of where

the photons land on the water, with and without the black hole.

A video of the black hole in the underground cistern is provided here:

As I mentioned at the beginning, taking the scene above and turning it into a hologram requires opening some black boxes. Firstly, I needed to implement the Chimera script within my raytracer; however, this did not prove to be a large challenge. More interesting was the need to look at how the images of my black hole generated by the script are turned into a hologram. I won't discuss this in detail here because I discuss it at length in the video at the bottom of this page. Suffice it to say that when I dug into these algorithms, I discovered that all of them implicitly assume that light ray trajectories are linear - at least between the camera and hologram plane. As I am dealing with curved light ray trajectories, in order to prevent these algorithms from breaking it was necessary for me to place the black hole behind the hologram plane and to "turn it off" in front of it, so that light rays move along linear trajectories until reaching the hologram plane, only bending once they have passed it. This compromise prevents the algorithms from breaking while also enabling one to visualize the optical distortion of the black hole. This is illustrated below.

Further details (as well as a stereo 3D video of the resulting hologram) are provided in the video below:

References

- Luminet, J.-P. “Image of a spherical black hole with thin accretion disk.” Astronomy and Astrophysics, vol. 75, 1979, pp. 228–235.

- Philippe Gentet and Seung-Hyun Lee. “True holographic ghost illusion.” Optics Express, Vol. 30, Issue 15, pp. 27531-27538 (2022)

- Andrew J S Hamilton and Gavin Polhemus. “Stereoscopic visualization in curved spacetime: seeing deep inside a black hole.” New J. Phys., Vol. 12, 2010

- Gröller, E. "Nonlinear ray tracing: Visualizing strange worlds." The Visual Computer 11, 263–274 (1995).

- Jensen, H. "Realisic Image Synthesis Using Photon Mapping." 2001.